Polartec Alpha Direct - Unlocking Castelli’s Breathe-first Paradigm

Introduction: The Unglamorous Side of Thermoregulation

This is how we convert stored energy (carbohydrates and fat) to work. A kW is a kilowatt, 1,000 watts. This is not a trivial amount of energy.

All-conditions cycling garments have long optimized for warmth and weather protection, but not for heat balance. Every watt we put into the pedals creates roughly four watts of waste heat. At endurance outputs - say, 250 W sustained - that’s a thousand watts of thermal load the body must shed to stay in equilibrium. Our muscles are only about 20–25% efficient; the rest is heat that must move through fabric, air, and sweat to escape. When these pathways are blocked - by windproof membranes, trapped humidity, or insufficient airflow - the system backs up. Core temperature rises, skin sensors detect overheating, and sweat glands open wide. The result isn’t comfort; it’s runaway sweat, evaporative inefficiency, and eventual chill.

Cyclists tend to evaluate layers by ‘warmth,’ but comfort depends on how effectively a garment lets heat and moisture escape as conditions and output change. In my deep dive into Castelli and Polartec’s solution for breathable wind and water protection, AirCore, I focus on the boundary layer tasked with managing exposure to the elements. If we choose boundary layers that are too porous or impermeable to both protect us from the elements and manage the peaks and valleys of our heat output, we fight a losing battle. AirCore represents a new standard that enables us to play with insulation layers in a more targeted way than before. Meaning, AirCore’s intentional micro air permeability can be tuned through base layer structure and properties to achieve the insulation–evaporation balance we need. The pieces we combine into a two- or three-layer system must be purpose-built for regulation; my focus here is on systems that maintain equilibrium from 10 °C to −15 °C through changing intensity, wind, and humidity.

Super Thermo Long Sleeve with Inlay, constructed from polypropylene - link

Intensity drives sweat rate and how it is established when we set out to ride. Most riders intuitively understand that our sweat rate isn’t fixed - it’s a self-adjusting feedback system driven by the balance between heat we produce and heat we shed. Power output determines the body’s heat load; wind exposure and garment permeability determine how efficiently that heat escapes.

When airflow or fabric resistance limits evaporation, the body senses rising skin temperature and humidity, and sweat glands ramp up production in an attempt to restore equilibrium. In effect, poor evaporative efficiency drives higher sweat rates, not because we’re working harder, but because the body is fighting to cool itself through a blocked system. Well-tuned layers let evaporation keep pace with heat production, stabilizing sweat rate and comfort even as effort or conditions change.

Fishnet Foundations

Fishnet base-layers create structured pockets for vapour to accumulate in and and flow through. In order to maintain a balanced microclimate around our skin, we won’t get very far with a fishnet layer alone. This should be obvious - it’s more not-shirt than shirt - and this is a good thing from a consumer awareness perspective: the product more or less tells you how to wear it. Working with a fishnet element means we need to think about how our system elements function. We want a bit of a barrier over a fishnet structure to modulate vapour flow/circulation, and just enough evaporative cooling from the skin’s surface to prevent our sweat-rate from ramping up.

Three angles stand out regarding fishnet’s contributions to the evolution of breathable insulation layers.

The fishnet base layer drives the user to realize that ‘dry skin’ is fundamental to staying warm across a range of intensity, energy output, and wind exposure. Fishnet’s primary function is to separate damp fabric from contact with the skin.

The fishnet base layer explicitly shows the user that empty/negative space - air space - is implicated in thermoregulation.

The fishnet layer cannot pretend to form a barrier to wind penetration to the skin, and is self-evidently not a stand-alone layer; it is always part of a system.

A second layer over a fishnet base-layer has at least two jobs:

Provide a boundary layer to prevent vapour from flowing away from the body too fast

Be permeable enough to allow vapour transmission without condensing

Block wind (sometimes)

I was introduced to Brynje’s classic Super Thermo polypropylene garment this top more than 15 years ago, while selling nordic / XC ski clothing at a local shop over a winter season. Numerous fellow staff recommended this top for my skiing and winter cycling needs, and it only took one or two outings to understand why it worked so well.

My learning curve with the Super Thermal primary involved pairing the top with a suitable second layer. Polypro and fishnet weaves are not stretchy, so even if I wanted to, my top wouldn’t have fit over another layer. It has always been against my skin, and I’ve experimented with a broad array of second layers over hundreds of rides. The layering combination I found most effective with my Brynje fishnet was my lightest merino or synthetic base-layers. I had a very thin, 150 gsm, Ibex merino layer I used until it fell apart, and a tighter weave Icebreaker 150 gsm. Ibex was superior to Icebreaker from a weaving perspective back in the early 2000s, and the layer I used was open enough to see through it far more readily than its Icebreaker ‘equivalent’.

First Wave Architecture

The depth of ‘air pocket’ a fishnet or mesh base layer forms matters because it determines how much air the layer can contain / manage. When I write ‘air’, remember: ‘air’ is actually vapour, which is moving energy; it’s our heat. The deeper each air pocket is, the more heat it can contain. I wore my sleeveless Brynje fishnet under a normal short-sleeve jersey once on a day around 20C, and I overheated wildly. At slow and moderate speeds the air penetration through my jersey wasn’t balancing the heat being trapped between my skin and the jersey. I had to take the fishnet off. In contrast, Castelli’s Pro Mesh base layer is extremely thin. It has perceptible perforations across its surface, which allow vapour to pass through freely, but it’s too shallow to trap air to any meaningful degree. In addition, as sweat rate saturates the garment, it holds sweat against the skin across more surface area than not (perforated / negative surface area), which translates to evaporative cooling.

The principle I’m attempting to get across here is that the depth and volume of negative space a base-layer’s structure creates amounts to ‘loft’, which is implicated in thermoregulation in relation to the rate at which exogenous air interacts with ‘trapped air’, i.e., ‘circulates’.

As evidenced by the contast of Castelli’s Pro Mesh and Brynje’s fishnet, the structural depth and volume of negative space within a base layer determines how it will interact with other layers that comprise our system. While fishnet and fishnet-like structures with varied negative space depth and volume have clearly been deployed commercially for quite some time, from what I know, Brynje’s offerings represent the upper end of negative space volume within the fishnet / mesh category. I would speculate that scaling up ‘chord diameter’ to increase negative space depth hits a threshold in terms of negative space area. Meaning, if you want to amp up the air pocket depth, you need to make the positive material (chords) larger in diameter (they are round), which doesn’t just increase depth; it also reduces negative space area. The area of the fishnet’s holes have to scale in proportion to the depth of each hole; this must be where diminishing returns kick in. This is why fishnet’s loft is constrained by its architectural design.

Loft: Let’s talk about that

In traditional outdoor insulation theory (mountaineering, sleeping systems), ‘loft’ implies stationary air trapped within a composite structure that resists conductive heat loss. Our bodies strive to maintain our typical sleep temperature, and while all kinds of physiological processes are being ‘powered’, including our brains doing a significant amount of work overnight, waste heat output is low. As ambient temperatures drop around us, we go from heat-shedding at the hottest end of the range - sleeping in a starfish position to keep each limb’s heat from transferring to other skin surfaces - to maximal heat retention in the foetal position, which places body parts against body parts to the maximum extend possible, reducing surface area for heat loss as much as possible (see Dan Timmerman’s leading insights about this topic). The technologies we use to manage heat retention between these poles need to slow the rate of heat loss from the body to the ambient air and ground below us. Meaning, ‘heat retention’ is a bit of a misnomer; what we’re talking about is controlled heat dissipation.

In extreme cold, around and beyond -40C, the goal is slow transfer of body heat to external environment by creating a microclimate around us. It might be most helpful to think about us trying to manage our steam.

Picture a nordic ski racer in a skinsuit racing a sprint event at the Olympics. These racers put out epic watts of waste heat. If I were to speculate, I’d put this number well above 2kW. When these skiers complete a race, steam is visible radiating from their bodies. The hotter air is, the more water it can hold = humidity. So if our skier is blasting 2kW heat, this hot air can contain several litres of water vapour per hour.

If they put a down jacket on immediately, this steam will push into the down’s lofted air space, and that volume of space in relation to the jacket’s external surface temperature determines how long the steam remains vapour, radiating gaseous water away from the body, versus condensing into liquid water.

For illustrative purposes, if we contrast a down puffy jacket against a waterproof membrane shell jacket over our Olympic skier, the physics at play become more evident. The membrane jacket’s fabric will have steam radiating against it on the inside, while the outside will have cold ambient air acting on it. At -20C, the jacket’s outer surface is only going to be ‘not-cold’ if the steam hitting it on the inside can raise its temperature and hold it there, and as vapour either passes through it’s membrane or doesn’t. If vapour is ‘shocked’ as it interfaces with the jacket’s cold inner surface, it will FREEZE on that surface. Once frozen, the ice will prevent vapour transmission through the membrane. From that point a few things can happen, but we’re more interested in the physics of loft here; let’s bring that back to the fore.

The shell membrane jacket exemplifies a situation where there’s no physical structure slowing the rate of steam dissipation from body to outermost surface interacting with the environment, which is where our ‘dew-point’ resides. The skier in a shell jacket has their dew-point close to their body, so the thermal mass and intensity meeting cold boundary layer is too extreme. Whether their vapour remains in the gas phase or condenses depends on how gradually its temperature and pressure drop as it moves outward. The name of the game, which folks working on sleep systems understand very well, is how we achieve the energy gradient required to match body heat output and environmental factors.

Loft, in this context, is the physical buffer that stretches that gradient, the distance over which vapour can cool and diffuse before hitting a surface cold enough to force condensation.

On this understanding, it’s clear how a down puffy jacket functions: it creates a very deep gradient buffer, but one designed for still air, not moving vapour. Down clusters form an enormous internal surface area that traps heat superbly, yet the same structure constrains air movement. In an endurance context, that means vapour cooling happens inside the insulation rather than through it, condensation and frost forming within the baffles instead of passing out.

While our skier will undoubtedly feel more comfortable in their down puffy right after a race, they’ll also ruin its insulating value within minutes by saturating it; this is often called ‘wetting out insulation’. The jacket’s deep, sealed loft traps vapour faster than it can diffuse outward; once condensation forms inside the down clusters, the structure that held warmth collapses. In practical terms, this isn’t generally going to be an issue, as the skier will change out of their wet clothing soon, and as their heat output drops drastically.

In static systems like sleeping bags, our energy gradient buffer (down loft) is filled with still air. When our skier introduces a whack of heat and vapour into a high-loft down puffer, they’ll be warm as they steadily reduce their jacket’s ability to maintain a heat balance.

In active systems, our energy gradient buffers are filled with moving vapour. The goal isn’t to trap it but to give it room to evolve; we need to slow the thermal and moisture gradients so the steam doesn’t shock-freeze inside the garment. That’s the physics of comfort: keeping the dew point out in the fabric, not against the skin. In the sleep system domain folks will often talk about ‘moving their dew-point out’, away from their moisture-sensitive insulation.

New Paradigm: Active Loft

There are circumstances within the cycling domain where heat output is very high, where our output drops off drastically, we need to manage the microclimate we’ve created, and we don’t want to ‘wet-out’ an insulating auxiliary jacket. I’ve been writing about this in my work on Castelli’s winter kit for years, and I’ll follow this post with one about dual-use auxiliary jackets. Before we transition back to Alpha Direct, let’s close the loop on the physics principles at play.

Once we stop thinking of loft as trapped air and start seeing it as a diffusion gradient for heat and moisture, a whole new class of fabrics - like AirCore and Alpha Direct - make sense. They’re not warm because they hold air still; they’re effective because they let heat and vapour move just slowly enough.

Within this paradigm, loft and the concept of ‘crushing insulation’ moves to the fore of how we assemble our cold weather systems. Consider base layers we’d consider ‘typical’ in cycling: do they have visible loft structures? Not really, right? That doesn’t mean they’ve had ‘zero-loft’, however; only a perfectly flat textile would qualify as that, and silk is the closest example I can think of. We don’t use silk for active base layers.

Think back to the two merino base layers I reference above: the better of the two 150g types I’ve used with fishnet differed in terms of porosity. The Icebreaker piece was ‘flatter’ / ‘smoother’ than the Ibex one, and it didn’t work as well. The Ibex’s porosity equated to small-scale loft. And because it was a thin knit, it wasn’t ‘crushable’. This means it maintained consistent loft whether I placed a very tight jersey over it or a loose one.

If you think about it, we’ve been layering textiles with varying amounts of loft / varied loft structures all these years. A very porous and relatively low loft layer like the Brynje fishnet would be covered with a less porous and lower loft Ibex merino layer. Over that would be either a long-sleeve jersey with whatever weave for porosity or a protective layer like the Perfetto RoS 2. If we used a Polartec fleece layer within a system, it would have all sorts of small-scale loft achieved by its tangled microfibre structure. Castelli has utilized numerous types of microfleece in their tights and jackets for years, some of which have visible 'loft’: Polartec Microgrid. Note, I wrote ‘microfleece’ and ‘microgrid’; these textiles have been designed for tight layering.

Micro loft describes the small-scale, resilient pile or knit depth within tight-layering textiles: enough structural height to preserve a thermal gradient, but not enough volume to slow vapour transport. It’s the form of loft that survives compression without losing function, which is why it’s flown under the radar in cycling for decades.

Returning to the main plot, we’ve worked through how loft is heavily implicated in heat energy interactions with our clothing. As cyclists, we have limited experience working explicitly and intentionally with loft as a system element. In the active, high-flux domain of winter cycling, we need to understand ‘loft’ in a new way:

In the context of high-energy-flux cycling, ‘loft’ isn’t about ‘trapped air’, but the volumetric capacity that enables regulated air exchange.

The space between lofted textile fibres becomes an active mixing chamber: warm, moist air leaves as drier, cooler air enters. If that space collapses, regulation fails.

Traditional loft → designed for retention - still air, slow conduction (sleeping bag logic)

Down puffies, mountaineering sleep systems

Micro loft → designed for fit - warmth in thin layers, resisting compression (outdoor sport logic)

Fleece, microgrid, thermal jerseys, tight winter layers

Active loft → designed for regulation - volumetric exchange that breathes under load (NEW layer logic)

Alpha and Alpha Direct

Since micro loft is barely crushable, it only makes sense I’ve never heard a bike rider mention not wanting to crush their insulation while riding, with the exception in the context of hands and feet, which many will have realized suffer from insulation crushing. This is one of the reasons hands and feet are the limiting factors for fatbiking on technical trails in my region; I’ve talked about this elsewhere, and will address it more in the future.

Of course, other high-flux winter sports will also benefit from adopting ‘active loft’ solutions, and I expect nordic skiers to catch on at some point. Sportful makes a Gore Infinium jacket with 60g Alpha Direct lining, which will work pretty well. I expect they will transition away from Infinium to AirCore before long.

Alpha Direct

These weights/AD designations might give the impression AD is like down or wool: you have more of it, and it’s heavier. This isn’t the case: any given weight can vary in construction.

I can’t think of a insulation textile as exceptionally effective at thermoregulation, yet wholly off-the-radar for cyclists as Polartec’s Alpha Direct. Whether you’re well in the loop or blissfully ignorant, read on; you’re likely to get something useful out of this. I won’t dive directly into Alpha Direct (AD) and how it works right away; the idea I’d like to register first is that AD is fundamentally an innovative and important construction method that enables a broad range of breathability and insulation tuneability. Polartec’s innovation in construction method builds off the strengths and weaknesses of a (very old) legacy technology: fishnet.

Alpha Direct strikes me almost radically different from fishnet textiles because it breaks the coupling of negative space depth and area. This is achieved through what I can only assume is very complicated manufacturing. If my assumption is grounded, this would explain the Alpha Direct’s high cost.

My first exposure to Alpha Direct was in fall 2021, when my Castelli Unlimited Puffy arrived. I ended up writing a detailed piece about the jacket and what it represented in the domain of active outdoor jacket innovation, which remains highly relevant. In my conclusion I wrote,

As strange as this sounds, the Unlimited Puffy could represent an early sign of a paradigm shift. As innovation in textiles marches forward, Castelli continues to experiment and push boundaries within the cycling garment domain. Other brands wait and see, Castelli leads. This is why it’s possible for me to receive a piece like the Unlimited Puffy and not recognize it as similar to anything I’ve seen before. And since folks don’t often feel comfortable throwing down their hard-earned cash for products that don’t fit into familiar frames of reference, innovative products often wind up hanging out in the background for a while until a core user-group becomes all about it, and the cat climbs out of the bag. This is what occurred with Castelli’s ground-breaking Gabba rain jersey; it took years for the general riding market to understand the piece and begin to purchase them. In the meantime, it was a staple across the pro ranks, and was imitated by numerous other brands.

If you’ve read my piece on Castelli and Polartec’s AirCore innovation and launch, you’ll note I make the same point about early adopters and the lag to the mainstream. While the Unlimited Puffy opened the door into the world of Alpha Direct, it posed as many questions as it answered. How good could Alpha Direct be if paired with other wind protection layers? How well could it serve as a dual-use insulator - on the bike and as part of a sleep system?

Castelli introduced their Cold Days 2nd Layer in Alpha Direct in 2023. Constructed from 90gsm Alpha Direct, Castelli describes the fabric as a “high-loft active insulation made from recycled PET”, with “maxum breathability”. I agree. It took until fall 2025 to get my hands on one, and as of this writing I have 5 rides under my belt in it, more than 15 outdoor sleeps, and one bikepack, where I rode in the layer, then slept in it.

AD's genesis is the result of clear problem definition the US military shaped, and Polartec acted on. Discovery Fabrics, a fantastic Canadian textile vendor, is the best source I’ve encountered regarding AD’s development and variants. If you have a general interest in learning about the properties, strengths and weaknesses of textiles, for apparel or gear, you will always find the most grounded and direct information coming from raw material vendors. They have a vested interest in helping their customers select textiles that meet their needs and expectations, and have little interest in marketing language. This is why you’ll see vendors like Discovery Fabrics publish copy like this:

The open knit of Alpha Direct does not repel the wind in any way! Often it is worn alone but for any wind or rain protection, it must be partnered with a technical shell such as Polartec Neoshell. (source - link above)

As I write above, it isn’t necessary to tell customers that fishnet garments don’t block wind in any way. One of the coolest things about Alpha Direct is that the label doesn’t actually refer to one geometry/composition. None of them will be suited to cold wind exposure as standalone garments, but that won’t necessarily be obvious from looking at them.

Alpha Direct is more of a construction method than a specific textile. This means that many variations are actually out there, and some of them are proprietary. For example, Mammut has just released a custom piece with Polartec built from polypropylene instead of PET/polyester. Intended as an explicit next to skin layer, the use of polypropylene provides a hydrophobic layer for use during intense, cold-weather activity. As with polypro fishnet, the Mammut garment will enable vapour to move through the open mesh structure and into the next layer. The vest itself stays warm and dry against the skin; it is not capable of absorbing water. In my experience, polypropylene is less stretchy and feels rougher than polyester against the skin. I suspect this is one of the reasons Polartec isn’t using polypro for AD in general.

AD’s construction consists of two main elements knit together, which can be adjusted in tandem to achieve the functional properties sought:

Mesh Core (base structure): Thin, highly durable, woven or knit base provides the level of permeability, upon which loft tufts are placed.

Porosity (or openness) of the mesh is a key variable that determines the fabric's overall breathability and stability.

Yarn Type/Density of fibers used for the mesh base can be adjusted. A tighter, finer knit offers more stability and slightly less air permeability, while a looser, more open-gauge knit maximizes airflow (high porosity) for ultra-high-output activities (like the Mammut AD vest).

Impact on Stability: The mesh is the scaffolding. A denser mesh provides a more robust anchoring platform, which can increase the overall durability of the fabric, but also slightly increases weight.

Loft Fibers (insulator): Tufts of soft, high-loft fibers permanently anchored to the mesh base. These fibers are crimped and arranged to trap air and create the thermal layer.

Denier and Crimping (thickness and waviness) of the fibers determine the insulation's volume and ‘springiness.’ Higher crimp and denier create greater loft, trapping more air for maximum warmth and improving the fabric's ability to rebound after compression

Tuft Density (stitch rate) dictates how densely the loft fibers are anchored to the mesh base per square inch. A high tuft density maximizes warmth but slightly reduces air permeability, while a lower density is often chosen for garments designed for intense, high-output activity.

Impact on Moisture Management: The fiber's material composition (e.g., standard recycled PET polyester vs. hydrophobic Polypropylene) is adjustable. This choice fundamentally dictates how the fabric manages sweat, affecting its ability to stay dry next-to-skin during varying activity levels.

As discussed above, fishnet is a mesh structure that relies on additional layers to ‘trap air’. Alpha Direct mesh cores are more complex geometries than fishnet, and their pores are smaller. While fishnet has ‘one move’ for creating negative space for air, AD has two moves: the ‘micro’ pores of the mesh core structure, and the ‘macro’ pores that constitute the negative space between the garment’s loft fiber tufts.

The Direction of Loft: Single vs. Double-Sided Construction

If the variability of mesh core and loft fiber construction and mixing wasn’t enough, there’s also the small matter of AD being constructed to provide loft tufts on both surfaces, versus one surface. This is perhaps the most obvious visual difference between AD variants and is key to a garment’s intended use.

Single-Sided Loft

This is the most common active insulation format, and the one used in performance pieces like Castelli’s Cold Days 2nd Layer.

Structure: Loft fibers are anchored to the mesh core and extend only outward, usually facing away from the body. The mesh core itself is smooth and sits against the skin or base layer.

Function: This construction is designed to be paired with a shell (or a woven outer face fabric). It excels at active temperature regulation, providing maximum breathability because the smoother mesh side rapidly moves moisture away from the body, and the outward-facing loft traps air under the shell.

Trade-Off: The loft is exposed, making it susceptible to snagging, pilling, and damage if worn as a standalone outer layer.

Double-Sided Loft

Structure: Loft fibers extend from the mesh core in both directions, creating a soft, high-loft surface on both the interior and the exterior of the fabric.

Function: This variant is intended for maximum warmth and comfort, often used in thicker fleece mid-layers or casual garments. The insulation is more robust, but the overall breathability is lower due to the increased density of material on both sides.

Trade-Off: While incredibly comfortable, the double-sided loft packs down less efficiently and is slower to dry than the single-sided variant. It is best suited for colder, lower-output activities where passive heat retention is the priority.

User Experience

The Cold Days AD layer is an effective, important element within Castelli’s drive to enable comfortable and safer all-conditions riding. The Cold Days layer’s tufts are on its exterior face, which places the majority of its lofted negative space between its mesh core and the layer over it. Wearing a very tight layer over it will crush its insulative architecture; I avoid doing that.

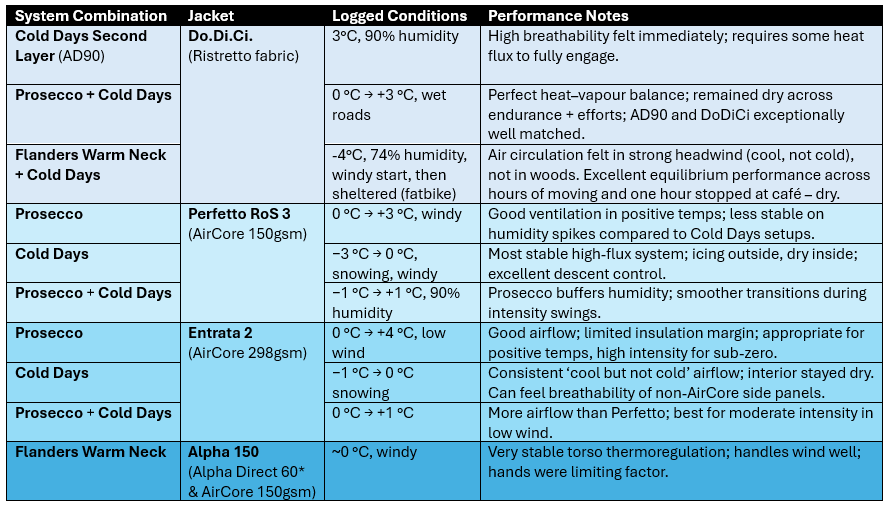

Table 1 - Insulation / jacket permutations and rider experience observations

How does it work when used alone under a jacket like the new AirCore Perfetto RoS 3, or over a thin base layer like the Prosecco with the Ristretto Do.Di.Ci. jacket? I’ve been collecting data from rides in the piece over Fall ‘25, and have a good sense of its performance. On many occasions I was out of the house wearing my 700-fill down jacket before rides, then changed into a Cold Days / AirCore or Ristretto piece thinking I had 50% probability of being warm enough during my ride. On every occasion I’ve been comfortable, and in zero occasions have I been wet inside my jacket. The Cold Days works exceptionally well directly against the skin or over a base layer.

Across dozens of sub-zero rides this fall, I tracked the behaviour of each system combination in real conditions. These ranges aren’t theoretical; they’re the actual envelopes where each combination regulated heat, humidity, and airflow predictably. Table 1 captures all the combinations I’ve tested through fall 2025. I’ve not been cold once, and as you’ll see below, out of 10 combinations ALL WORKED. If you think about it, this is kind of wild. Technically, it is testament to AirCore and Ristretto’s ability to themoregulate.

I’ve also extensively used the Cold Days top for sleeping outdoors (more on that here). By itself, its cozy, and combined with a layer (I use my Cumulus Climalite Pullover, which uses Climashield Apex synthetic insulation), it functions as a key component of my sleep system. As a dual-use piece, I can ride in the Cold Days all day, then sleep in it; no need for a separate sleep shirt. While not technically ‘hydrophobic’, Alpha Direct strongly resists retaining moisture; coming out of the washing machine (high spin), it is slightly damp. I wouldn’t hesitate to put it on straight from the machine and let it dry while wearing it.

Based on my experience, it’s a no-brainer to recommend the Cold Days Second Layer to anyone and everyone who wants to ride more comfortably in cold conditions. ‘Cold’ is relative; if you never need more than a thermal long-sleeve jersey, it’s not for you. If you wear jackets with wind protection, it would make sense for you.

Conclusion

What all of this points to is simple: cycling isn’t a static thermal environment. Our heat load swings minute by minute with power, wind, terrain, and humidity, yet most garments are still designed around fixed temperature ratings. They’re warm when we produce little heat and overwhelmed when we produce a lot. The real need isn’t ‘more warmth,’ but layers that preserve a stable gradient between our bodies and the environment, allowing heat and moisture to move outward at the right rate as conditions and output change.

The underlying logic isn’t new. I’ve said for years that no bike performs on frame weight or geometry or stiffness alone; performance emerges from how these elements interact with the rider in motion. Winter layering is governed by the same principle.

Heat balance isn’t a property of any one fabric; it’s how the system adapts with us to maintain a stable gradient through flux. AirCore and Alpha Direct don’t ‘keep you warm’; they keep the gradient intact and represent the difference between fighting your clothing and riding in equilibrium.