Continuity and Failure in Winter Thermoregulation

On Dec 27 and 28, 2025, I compared core protection systems under comparable sub-zero winter conditions. My intention was to find the edge of a few thermoregulation boundaries. In this Matter Lab Note, I link what I experienced to thermoregulation science from researchers who study human performance in extreme environments. This is not a jacket review. It’s a field framework to identify dominant heat-loss pathways and choose interventions that restore continuity. My goal is to make this repeatable, so other riders can diagnose their own failure modes and fix them in real time.

Background

A few pieces of common knowledge shape how people dress for cold outdoor activity. ‘Keep your core warm’ is widely understood, but it sits awkwardly beside ‘sweat and die,’ a blunt phrase that points to a real winter failure mode: moisture becomes a heat sink the moment you stop producing power.

Hockey and nordic skiing are popular in Canada, and both involve continuous gross motor work with a lot of limb movement, which generates substantial waste heat. Winter cycling is different. The work is mostly waist-down and within a narrower range of motion. Hands are relatively static, wind-facing, and in contact with metal parts. In other words, cycling combines sustained heat production with persistent peripheral exposure, often far from shelter.

While keeping the core warm on a bike in winter isn’t hard, striking a balance of insulation, wind protection, and breathability across a broad range of conditions can be. The goal isn’t to avoid sweating at all costs, but to reduce the onset of sweating as much as possible, and clear sweat from the system in a timely fashion while on the move (and while static, as a contingency - more on that later).

Let’s be precise with our terminology here. As long as we live and breathe, our bodies output metabolic heat and water vapour from our skin. In heat-transfer terms, there are two broad categories of heat loss. The first is sensible heat loss, where heat moves down a temperature gradient without a phase change. This includes convection to moving air (wind chill), radiation to the environment, and conduction through direct contact. The second is latent heat loss, where heat is consumed by a phase change, primarily the evaporation of water.

Sensible heat loss is often referred to as ‘dry heat loss’, heat loss that is not carried by evaporation. We’ll see an example of this mechanism below, during my Dec 27 test.

While moisture is always present, the crux of an effective clothing system is whether evaporation can keep up when sweating is unavoidable, and whether the system allows that moisture to move outward and away on a relevant timescale. My Dec 28 test shows how my system did that.

Sweat is an effector, not a synonym for vapour. We are always losing moisture invisibly, but sweating is an active response triggered to regulate core temperature, and its cooling power comes from evaporation. Airflow matters because it carries humid air away and supports evaporation, which is what actually removes heat.

For winter riding, the practical goal is to control both categories at once: prevent uncontrolled sensible heat loss from wind and air exchange (controlling convection via textile wind resistance), while preserving enough permeability and venting that latent heat loss can occur (evaporative cooling + vapour transfer) when sweating is unavoidable, and moisture does not accumulate. As we’ll see below, my Dec 27 test was dominated by uncontrolled sensible loss at my arms. In contrast, my Dec 28 test was dominated by latent loss and moisture clearing.

Thermoregulation Boundaries

In winter kit testing I often aim to identify boundaries by pushing pieces in scenarios I suspect might lead to system failure. Here, a boundary is the point where a clothing system stops self-correcting and begins to drift, either toward sweat loading or progressive cooling.

In an ideal scenario, thermoregulation functions so well that heavy sweating is minimized and the system stays near equilibrium. At high wattage on a bike, that usually requires minimal insulation and enough air exchange to shed dry heat via convection. The more varied the terrain, environmental conditions, and power outputs are, the more we need to manage both sides of the problem: reduce unnecessary sweat production, and support the outward transfer and clearing of moisture, while keeping the core warm enough to protect hands and feet.

Core-first thermoregulation is the control logic here, the physiological system that prioritizes core temperature before extremities. It is easy to assume this only means heat retention in winter. It does not. A small set of ‘primary effectors’ dial up or down to hold our core set point under changing conditions. For riding, the practical effectors are sweat production, shivering heat generation, and blood flow control to the skin and extremities. In practice, a boundary can be perceived when these effectors are still working, but our clothing system no longer supports them.

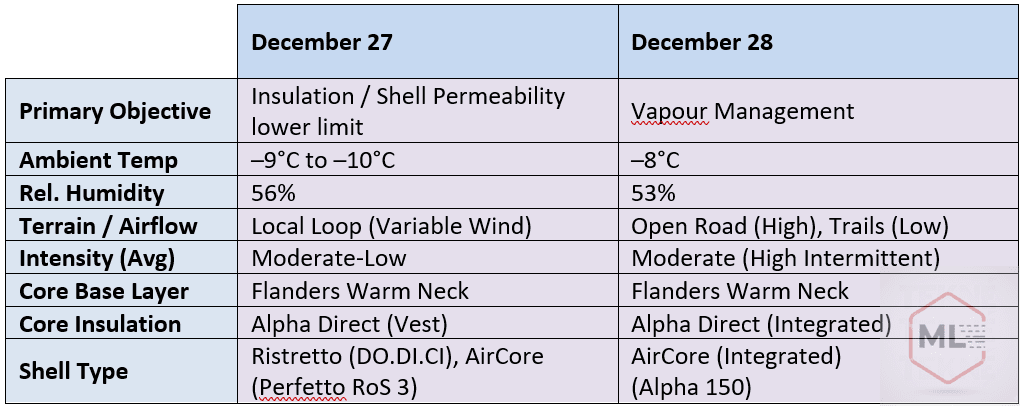

Mt tests focused on the dynamic between core temperature, forearm, and hand warmth. Lower body kit and headwear were held constant. I also used two control elements to keep signals clean.

Control 1: Castelli Espresso 2 AirCore gloves - breathe well and resist wet-out under higher effort. That matters because it reduces a common confounder: if my hands start to chill, it is less likely that the gloves are failing, and more likely that something upstream is driving the change.

Control 2: Castelli Flanders Warm Neck base layer - medium-weight, high-collar base layer with good permeability. For fatbike riding, the neck coverage is a useful balance between protection and heat management.

My specific curiosity centred on the DO.DI.CI jacket and the permeability of its Ristretto fabric. On the 27th, I planned a two-hour loop in Ottawa with variable wind exposure. I brought my Perfetto RoS 3 as a swap option.

I had ridden the DO.DI.CI plenty, but not down around −10C. I expected some air penetration into the forearms for the first 10 to 15 minutes. The questions I wanted to answer were:

Would maintaining a dry and stable core temperature offset excessive convection from my arms.

If answer to #1 was no, would a forearm cooling trend propagate upstream to my core?

If answer to #1 was no, would a forearm cooling trend propagate downstream into my hands?

If my core temperature was strained, would I be able to tell?

I was willing to push the limit with my arms, but wanted to ensure my core was protected. I started with the Fly Direct vest, which combines Alpha Direct active insulation with a tightly woven exterior. Across both days, the main variable was outer-layer air exchange at the arms, with the vest used as a controlled intervention. The gloves were a control at both ride temperatures, and if my hands chilled, it would not be a glove problem.

The following day’s ride would be longer, slightly warmer, more physically demanding, and riskier. The risk was not the ambient temperature, it was the crash problem. A fall can flip you from an active heat-generating state to a static state instantly, and injury can prevent you from restarting heat production.

My aim was to determine whether the Alpha 150 jacket’s incorporated insulation would handle a wider range of conditions, including intermittent high power and lower airflow in trails. In the past, wearing more than the bare minimum insulation usually challenged heat balance, especially when effort spiked. This time, the system would rely on fabrics designed to tolerate broader energy and moisture dynamics.

phoyos

Ride Data: Thermoregulation Gradients

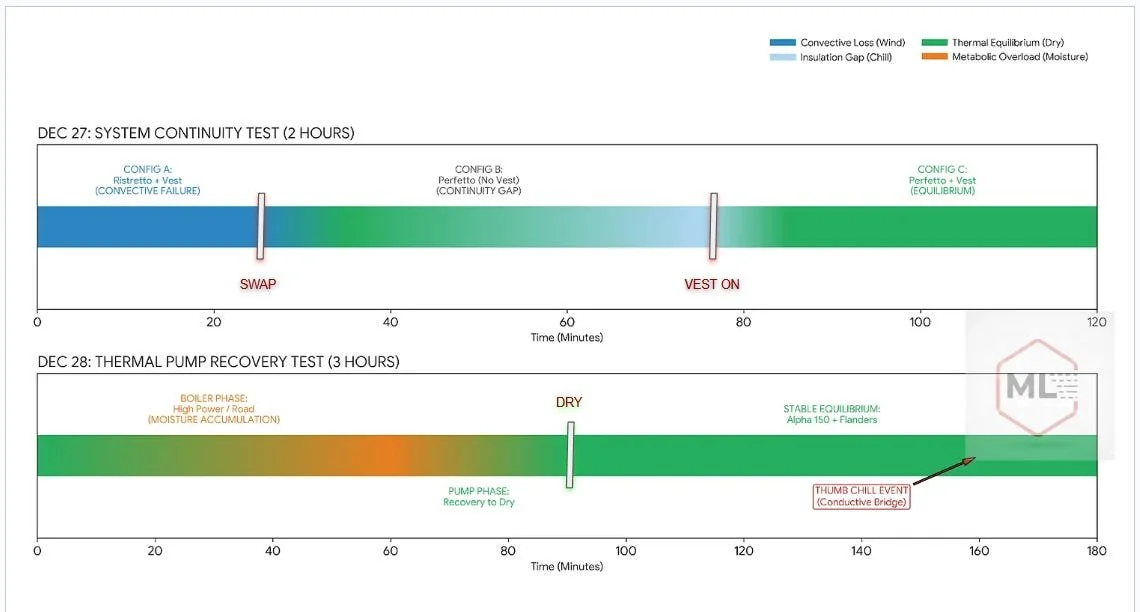

I translated my ride logs into a qualitative state chart. It does not depict measured core temperature. It maps perceived system behavior over time: wind-driven cooling (convective failure), localized chill (continuity gap), boiler phase (moisture accumulation), pump phase (recovery to dry), and stable equilibrium.

December 27 - System Continuity Test

The upper bar shows the Convective Failure of the Ristretto shell on the arms (blue). My hands were fine, but I could tell my arms were not going to warm up. Sufficient insulation at the core and hands was not enough to overcome low insulation and high air exchange at the arms.

At the 25-minute mark I swap to the Perfetto and leave the vest off. This resolves the arm problem. The bar shows a short recovery period as my arms level out, followed by a provisional equilibrium. Around the 50-minute mark my abdomen begins to chill. This is unusual, but not unheard of. At about 75 minutes I add the vest back on, which acts as a seal. I feel the effect immediately, and the return to stable Equilibrium is rapid. My hands never felt cold.

December 28 - Thermal Pump Test

The second timeline above depicts the Boiler Phase (orange), where high metabolic output outpaced vapour transmission and moisture accumulated in the system. The pivot point occurred at the 60-minute mark; as I moved into the trails, the Thermal Pump began clearing that moisture. By minute 90, the system achieved Active Recovery to Dry, and remained stable for the rest of the 3-hour ride. Note the red ‘Conductive Bridge’ marker, a localized failure that occurred despite a perfectly functioning core system.

Findings - Dec 27

1) Would a dry, stable core offset excessive convection at the arms?

No, not reliably. My core and hands stayed fine, but my arms did not recover until I reduced arm air exchange (swap to Perfetto). This suggests core insulation alone could not compensate for convective heat loss at the sleeves.

2) Would forearm cooling propagate upstream to the core?

Not in the time window I tested. I did not sense core strain during the Ristretto segment. The pattern looks like a localized convective failure I corrected before it could become systemic.

3) Would forearm cooling propagate downstream into the hands?

No. My hands stayed warm the whole time, which supports my glove control logic at this temperature.

4) If my core temperature was strained, would I be able to tell?

I could detect system drift (abdomen chill), but I did not measure core temperature and I suspect this was surface-level rather than a true core change. This result is non-conclusive.

Findings Dec 28

5) Would the Flanders Warm Neck base layer provide the optimum balance of insulation and moisture management?

For this jacket in these conditions, I don’t think so, based on repeated rides. The Alpha 150 blocks wind well enough that an Alpha Direct base layer is the better insulation option. When convection is well controlled, Alpha Direct is warmer for its weight and more compliant across changing effort.

6) Would mechanical venting be required to manage moisture?

Yes, I unzipped a bit a couple times before striking system equilibrium. Venting that exposes damp fabric to wind could create a brief localized cooling signal that encourages vasoconstriction. I did not measure this directly, but it is a risk worth keeping in mind.

Bonus: Why did one thumb get cold?

My right thumb got cold in the last 20 minutes. Since my gloves were not wet, evaporative cooling from wet insulation was unlikely. The more plausible cause is a localized conductive pathway into metal controls during frequent shifting, combined with lower power output late in the ride and reduced heat delivery to the periphery. My grip lock-on collars are metal, and I can feel them pull heat from my thumbs and index fingers when my hands drift too close. I run carbon bars and carbon brake levers to reduce conduction, but the shifter and dropper levers are still metal, along with the grip collars.

Conclusion

These two rides reinforced a simple point: winter cycling comfort is not a static state of ‘having the right jacket.’ It is dynamic management of heat loss pathways and moisture over time.

On Dec 27, convective heat loss at the sleeves created an early boundary at the arms. Core stability did not compensate for excessive air exchange at the forearms. The fix was to reduce wind chill, not to hope the core could push enough heat outward. The later abdominal chill was a separate continuity warning that resolved immediately once the vest restored the heat seal.

On Dec 28, the system temporarily loaded moisture during a high-output boiler phase, then returned to dry once conditions shifted, without requiring a kit change. The late-ride thumb chill was the reminder that localized conductive bridges can occur when the core system is stable.

Next Lab Note

In the next note I’ll isolate the thermal pump concept and managing heat and risk with an auxiliary ‘stop layer’. I’ll follow with dedicated follow-ons about conductive bridges at the cockpit and feet, and the design choices and behaviours that help manage the challenges of conductive heat loss.

Sources:

Gierszweski B, et al. Biophysical parameters of human thermoregulation in extreme environments. Frontiers in Physiology. 2024;15:1468153. doi:10.3389/fphys.2024.1468153.

Available at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11486477/