Down, Synthetic, or Both? Building Smarter Sleep Systems for Bikepacking

Down and / or synthetic insulation; it depends.

Enlightened Equipment Revelation Apex 50F / 10C Quilt

Intro

If you’re turning your attention to camping with your bike, any which way, you’re probably thinking about what you need for comfortable sleep; the whole idea is to have fun, right? Most of us can absorb one night’s bad sleep without being wrecked, but racking them up consecutively will definitely diminish physical and cognitive capabilities, undermining our ability to ride bikes safely, let alone in the fun zone. Whether your goal is to ride a bit and hang a lot at camp, ride a lot and spend the minimal amount of time stopped and sleeping, sleep quality matters.

A year ago I had no idea how good ultralight synthetic insulation could be, for sleep systems or clothing. I’ve been researching the topic a lot, building off winter ‘24-’25’s experience sleeping outside with a big synthetic mummy bag I can’t even fit onto a bike. I started writing this because I was delighted at the compressibility, weight, and comfort of the Enlightened Equipment Revelation APEX 50F quilt I purchased from Gear Trade in Alberta mid-summer 2025. I crossed my fingers that the quilt would pack as small as my down Seat to Summit Ember 10C quilt (now discontinued), and thus function interchangeably and as a supplement. The audience for a comparison of the two alone would be small, so I’ve worked up the ‘so what’ part of this post, which eclipses the quilt comparison. If you’d like to FFWD to the comparison, scroll down.

This post comes out of somewhere around 17 years riding and camping with a Frankenstein mix of gear, layered atop years of camping as a Boy Scout. Backpack, tent strapped to my frame, ultra-minimalist experiments that were laughably ill-fated (I once slept on a rock face with nothing but a silk sleeping bag liner and bug net for ‘comfort’ and ‘protection’). Riding to camp spots within 1-3 hours from home, I started experimenting with the bare essentials for survival, then pushed further out and worked into exploring and defining ‘the fun-zone’. As I learned from experiments and mistakes I steadily worked on bringing friends into the fray, and saw them struggle with all the same challenges I had. We were all spending tonnes of cash on bikes, kit, racing, travel; none of us were keen on throwing money at camping kit until we were confident we’d ‘get it right’.

While the majority of us aren’t racing anymore., we all still want to get it right and avoid burning money as we pursue bikepacking and bike-camping adventures. And, as friends have gotten into bike-camping, I can see everyone becoming inspired to develop the understanding and means to take on different styles of excursion, from bikepacking at the fastest rate possible through meandering exploratory expeditions.

Sleep systems are the hardest element to figure out, and I know first-hand how the sleeping bag you have might simply be too massive to fit onto a bike; that’s a problem! I owe a lot to folks like Dan Timmerman, whose blog cracked open the a whole new level of system thinking for me, particularly concerning sleep systems. Dan has also been generous with his time, answering questions over emails; thanks Dan! What follows is my attempt to pay that learning forward.

Background

I have a lot of storage capacity on my T-Lab X3. I made this fairly massive roll-top bag to fit my tent and entire sleep system across three seasons; my synthetic mummy bag alone would fill this space. This was the bag’s first trip, it looks better now!

Camping kit has evolved dramatically since the mid-20th century’s wool and canvas bedrolls, and the rise of ultralight (UL) backpacking, driven largely by a robust US-based cottage industry, has redefined what sleeping systems can be: minimal, modular, and optimized for performance. Early ultralight adopters leaned heavily on high-fill down quilts for their unmatched warmth-to-weight and compressibility (which remains the case today). But over time, the limitations of down - particularly in humid, wet, and variable environments, and associated with the breathability of down-proof fabrics and breakdown of down’s structural loft caused by packed compression - opened the door for advanced synthetic insulations like Primaloft Gold and Climashield Apex. These engineered insulating materials offer unique benefits in the context of standalone and layered systems.

Today, bikepackers are adapting and evolving UL principles in the context of even more challenging volume and weight distribution constraints (backpacks are relatively easy compared to bikes with bags that influence handling stability), often pushing insulation hard. While we’ve inherited a modular, resilient sleep system approach, misconceptions persist concerning variables at play, and bike riders need to navigate the pitfalls of ‘packing their fears’ while seeking economical options at the point of entry into bikepacking / bike-camping. Our bikes and kit are already really expensive, right?

I share below insights I’ve developed over the last 15+ years of dabbling in UL bikepacking before that was a term, and recent years sleeping outside all the time (literally). I’ve been learning a tonne from folks making solutions for the UL backpacking and bikepacking crowd, and am happy to channel them here. I’m also dabbling with make your own gear (MYOG) / DIY outdoor equipment as a new hobby, which has presented a fantastic opportunity to seek out information and insights from the most brilliant and innovative folks in the domain, which is a constant reminder of what it’s like to be a beginner in a new field of possibilities.

The Question: If I want to get into bikepacking / bike-camping, I need a down sleeping bag, right?

Maybe, maybe not. Anyone who says ‘yes’ to this, definitively, should not be considered a credible source of advice and wisdom.

The primary reason bikepackers default to down bags and quilts is that they are generally well-understood, broadly accepted, and easily accessible. Fastpackers and thruhikers are the closest analogs to bikepackers (especially racers) I am aware of, and many of them came to the realization a long time ago that synthetic insulation is more practical than down for moving fast and light. Are these folks also all over the internet talking about that?

Cowboy camping, under the stars, is a special experience, and my preferred mode.

Social media amplifies gearhead content that is often disconnected from reality. ‘10 Camping Gadgets You Need’ is the dominant voice, consumerism wrapped up in Gore-Tex (no shade on Gore-Tex intended), not nuanced discussion about insulation strategy.

Meanwhile, the folks making excellent gear - often in garages and small shops - aren’t doing shiny marketing. They are explaining physics, performance principles and dynamics, trade-offs, sharing design decisions, and being radically transparent. This is why they have really strong reputations within the outdoor gear community. If you’re already immersed in the world of ultralight and minimalist outdoor gear domain, you’ll likely know who I’m talking about: Dan Durston, Dan Timmerman, Ron Bell. Their credibility is rooted in deep design insight, technical rigour, and hands-on testing; they walk the talk. They are also all very open with technical information (see Ripstop by the Roll Podcast) and user-guidance, which you will absolutely NOT see from big brands. Cottage industry folks are able to lean into detail, because folks who rely on their kit out in the wilds pay attention to detail, seek it out, and become/are skilled.

When users need to know whether kit will work for the use-case they have in mind, they read closely, and learn. This enables cottage industry folks to sell optimized and cutting edge products to folks who are actually ‘clued in’. The same products will tend to work less well in the hands of beginners who lack experience and skills required to manage delicate materials, combine elements effectively, etc. This is why big brands don’t sell ‘the best stuff’ for ultralight (UL) use; they can’t. If they did, they’d deal with untold warranty nightmares. Full-circle, the most common / ubiquitous sleep system kit you’re going to see at stores like REI and MEC are designed for general and infrequent use by people who are not full-on gear nerds; they don’t need to be. This is totally fine and appropriate. However, it also drives the misconception that sleep elements are islands unto themselves. I.e., if you want a sleeping bag, you get the one that is the warmest you can imagine needing (packing fears) and lightest possible in relation to your budget, right? Then you get the lightest pad you can handle lying on, right?

Packing Fears in Practice

Wrong. Easy to write, hard to understand without experience. The ‘pack your fears’ mindset commonly drives sleep system choices, and it’s a known psychological pattern in both backpacking and bikepacking communities. Packing our fears in the form of sleep system elements manifests in the following ways:

Overbuying temperature rating: people who fear being cold often choose a bag/quilt rated far below the coldest conditions they’ll actually face — sometimes 10–20°C colder.

Ignoring system balance: sole focus on bag warmth, overlooking pad insulation, shelter placement, and layering, all of which can be lighter, more versatile fixes.

Packing extra ‘just in case’ gear: heavy liners, secondary blankets.

Why are these choices common?

Lack of experience: without time in the field, people don’t know how their body actually responds at night in varying conditions.

Marketing & specs: EN/ISO numbers feel like an easy, absolute metric, which makes ‘lower temperature rating is safer’ seem like the right move.

Fear-driven decision-making: cold discomfort is more memorable and dreaded than most other camp issues, so people overcompensate.

So what’s the big deal? Well, for backpacking people can size their pack up to match their level of fear/anxiety/inexperience, but bikes are more constrained. MTBs can only fit so much on the bars, frame, and seat-post (especially with dropper posts). If you’re overpacking sleep kit you’re compromising somewhere else: water (yikes….), food (oof…), protective clothing for extreme weather (dang….).

We tend to run into problems - including danger - when we bias toward minimalist gear and provisions at the cost of increased cognitive load. If we overdo our sleep system and force ourselves to be ultra-minimalist in other areas, we can often end up spending more energy preoccupied with managing water and onboard food, for example. Below are the primary downsides associated with trying to pack too much sleep system volume.

Weight and bulk penalties: heavier, more voluminous sleep systems cut into available space for other kit, or force more rack/bag volume.

Reduced versatility: over-warm bags can cause overheating in milder conditions, leading to poor sleep and more moisture buildup in insulation.

Missed optimization: the biggest efficiency gains usually come from fine-tuning all components - shelter, pad, quilt/bag, and clothing - not just maxing out one piece.

Modularity in Action

This is Polartec Alpha Direct 90gsm I bought 5 yards of, then cut a 2 yard length of to create a blanket I’m using here as a liner within my EE Revelation Apex, and will do modular things with - more to come on the site. I look forward to making other items: hat, socks, sweater, pants; they won’t be pretty though!

Writers like Dan Timmermann (Timmermade) and makers like Ron Bell (Mountain Laurel Designs) address modularity indirectly: they emphasize system thinking over chasing a single ‘warmest’ item. In their view, balanced setups are lighter, more adaptable, and perform more reliably across a range of conditions. If you want to work within your bike’s carrying capacity constraints, packing for hot summer conditions won’t tend to be particularly challenging. But if you want to venture out in variable conditions, especially over prolonged periods (like thru-hiking), you’ll need to focus on dual-use pieces of kit wherever you can. For example, a beanie you can wear under your helmet and while at camp is a good choice. One that is too thick for under a helmet isn’t a wise choice. Quilts that feature a slit to pass your head through in poncho-mode are similarly dual-use, a very sensible approach for hikers because ponchos work nicely with backpacks, while for cycling they don’t. However, both user groups might benefit from being able to wear their quilt at camp; this depends on whether the individual’s style is ‘get to camp and hang’ or ‘get to camp and sleep’. I’m more the latter, so I don’t need a slit in my quilt. However, for those who want one, between the two insulation types - down and synthetic - one is suited to poncho use: synthetic. It’s all about user requirements and preferences, in that order.

I’m developing a very versatile modular sleep system to cover the full span of conditions I sleep in, from the hottest of summer nights (at times beyond 30C) and coldest (at times -30C). The only way I’m going to do -30C is at home, which doesn’t entail schlepping my big synthetic mummy bag around. With that mummy, I use additional insulation layers within according to conditions, and cover myself up entirely with a handy blanket when the snow is blowing (similar to how people do tarp tacos). Ultimately, I will wind up with an ‘overquilt’ atop my mummy to move moisture away its shell, and protect against rain and snow. It will be a step short of a bivvy, and I will use it to develop experience with moisture management configurations I can apply while bikepacking and bike-camping in less extreme conditions. I.e., will cowboy camping be a viable go-to approach for summer when rain is unlikely, with just enough wiggle room for dealing with rain?

Down : Synthetic Quilt Comparison

Below: the revelation, literally and figuratively; the photos show the size, weight, and compressed size of my Enlightened Equipment Revelation APEX 50F/10C synthetic quilt (Regular Wide size) against my Sea to Summit Ember 50F/10C (Regular). As you can see, the Revelation is larger overall than the Ember. Each brand’s approach to closures and straps is similar, with the exception of the zipper that creates an enclosed foot box, which is 20”/50cm long. That adds weight, in addition to the quilt being larger overall.

Sea to Summit Ember 10C Regular down quilt atop Enlightened Equipment Revelation Apex 50F Regular-Wide synthetic quilt

My Ultralightsacks dry bag weighs 50g; the Revelation (395g) is on the left, Ember on the right (398g) - both weighed without straps, which is how I use them most of the time. It’s difficult to photograph packed dimensions well, but it’s fair to say the Revelation packed about 1/4” longer than the Ember, which is amazing given the additional size and zipper bulk.

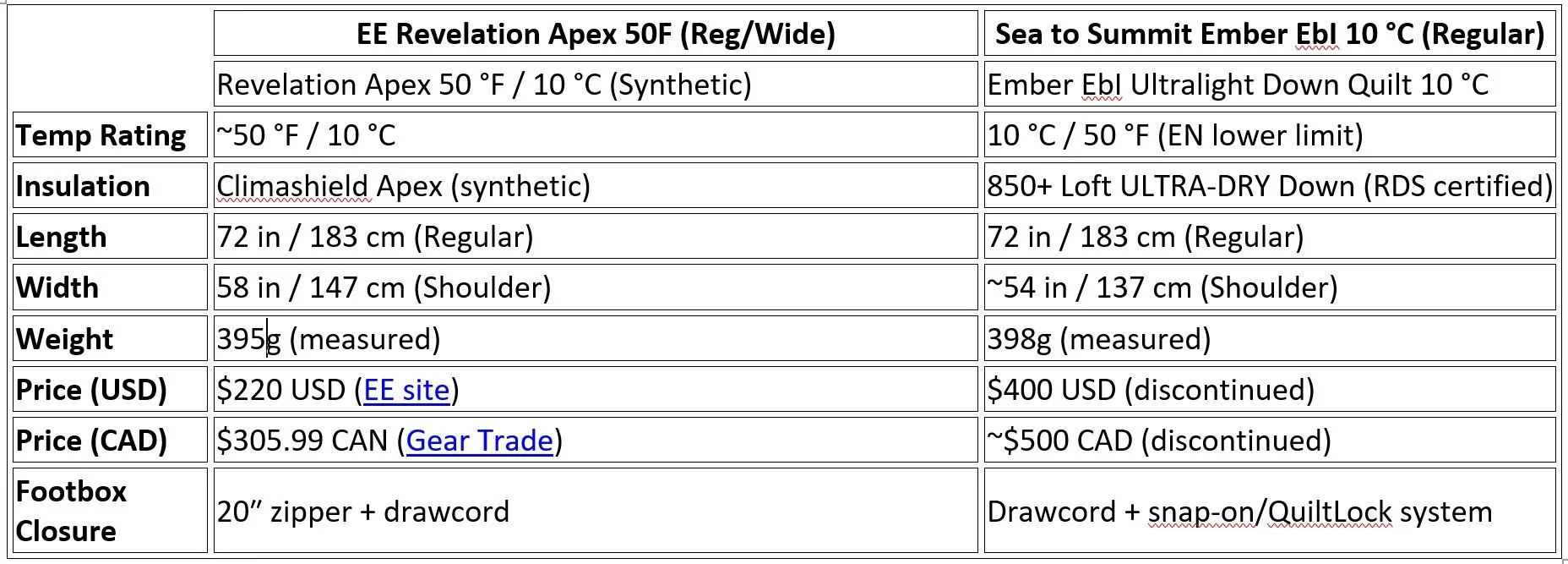

Comparison table

These quilts have the same comfort rating: 50F / 10C, nominally. The Revelation Apex 50F is rated by Enlightened Equipment’s own guidelines, not a standardized EN/ISO test. Its 50 °F / 10 °C label is best read as an approximation: most users will be comfortable in the mid-teens Celsius (high 50s Fahrenheit) and above, but at the lower edge of its rating you’ll likely need extra layers and an insulated pad.

The Sea to Summit Ember EbI 10 °C, by contrast, carries an EN/ISO temperature rating, meaning it’s been tested against the same standard used for sleeping bags. Its 10 °C / 50 °F lower-limit rating indicates more predictable performance, though true comfort for most sleepers will be a few degrees warmer. It’s more thermally efficient than the Apex quilt, thanks to high-fill down, but less forgiving if damp and considerably more expensive.

Specs are important, but don’t tell the whole story. As discussed in my post about down socks, foot comfort is heavily implicated in sleep comfort and quality, and the Revelation’s zipper footbox is superior to the Ember’s reliance on drawstring, straps and snaps. Consequently, the Revelation stays positioned on top of me better than the Ember the way I usually use it: no straps. The implication here is that your quilt is only as effective as its ability to cover you through the night. If you’re starting out at 22C at night, and expect the temp to drop to 12C, you might want your quilt open so your core temp can drop (necessary to get to sleep), then cover up as the temp drops. The Revelation’s zipper footbox closure lets you choose whether to have that security. If it’s not cold enough to worry about your feet, you also don’t need to worry about the quilt fully covering you all night; it can slide around and you’ll be ok.

No stitches are required to keep the Apex insulation in place within the Revelation.

The 850 down fill in the Ember is a more efficient insulator than Climashield Apex, assuming it is in good condition (dry, dry enough) and positioned well within the quilt’s baffles. You can see in the photo above that this is not the case; it never is except perhaps directly after I tumble-dry the quilt. In contrast, Climashield Apex doesn’t require quilting / segments, and lies flat as one sheet of insulation. It is generally understood that thickness / density varies across a sheet of Apex, so it cannot be considered ‘totally consistent’ in terms of insulation, and is thus not defacto superior to down in this regard.

After numerous nights testing and tracking data on the Revelation Apex’s performance, I’m convinced it is slightly less warm than the Ember when dry, assuming feet remain in the Ember’s cinched foot box. When wet, I don’t yet have experience. The Apex insulation is not as warm as the down, but it is close. The Apex’s shell fabric doesn’t need to be downproof, and as such can be chosen to optimize breathability, wind resistance, and air retention. In terms of feel against the skin, especially the feet, the Revelation feels doesn’t feel clammy, while the Ember often does. It is clear that the Revelation retains air more more than the Ember, which is counter-intuitive. You’d imagine the Ember’s downproof shell would very tightly woven, and thus retain air more; it doesn’t. What’s up with this?

The Ember’s shell is built from ultralight 10D ripstop nylon with durable water repellent (DWR), paired with a 7D liner (‘D’ refers to ‘denier’. This is a phenomenal resource for definitions). On paper this looks efficient: tightly woven, down-proof, and designed for minimum weight. In practice, though, ultralight fabrics are full of tiny pores and stitching holes. Air moves through them more freely than you’d expect, and with sewn-through baffles the down can also shift, reducing loft exactly where you need it most.

By contrast, the Revelation Apex’s synthetic insulation is a continuous sheet. It doesn’t require baffles, so there are fewer seams and holes, and the shell fabric doesn’t need to be down-proof. That means EE can prioritize breathability, wind resistance, and air retention differently, and in my testing, the Apex’s fabric actually holds air more effectively than the Ember’s ultralight shell. I feel this equates to a better regulated micro-climate.

Conclusion

The observations I’ve shared here are rooted in structured field use, which entails tracking conditions and subjective comfort night by night and testing the same systems repeatedly across varied conditions. My ongoing project centres around building a deep understanding of how equipment behaves in practice, and how behaviours ripple through the whole sleep system, and overall complement of gear.

My focus remains on combining the insights, best practices, and gear options from the non-cycling outdoor adventure domain into the cycling domain, where systems thinking encompasses complex gear-bike constraints and interactions.

Getting into bike-camping and bikepacking is complicated and overwhelming for most riders, and uncertainty drives fear; fear drives overbuying, overpacking, and at times the opposite: underpacking. The take-home from this comparison isn’t that one quilt wins and the other loses. It’s that we need to avoid treating insulation as a one-dimensional spec sheet and think in terms of systems. Down and synthetic each have trade-offs, and neither is universally ‘better.’ What matters is understanding how they behave under real conditions, how they interact with your pad, shelter, and clothing, and how that all comes together within the carrying constraints of a bike.

My Revelation Apex 50 has shown me that synthetic insulation can be as light and compact as down, with durability and moisture tolerance that make it a legitimate option for bikepacking and bike-camping, not a compromise. The Ember still has a slight edge in dry warmth-to-weight, but its limitations are clearer when you live with it night after night.

For riders trying to piece together their own kit, the message is simple: don’t pack your fears, and don’t buy into marketing that pretends any single item is the whole answer. Build a modular system you can trust, refine it with experience, and learn how each element contributes to comfort and safety. That’s where the real efficiency and freedom come from.

This is the perspective I’ll keep bringing to my testing and writing: not just reporting specs, but mapping how equipment actually performs in the field and how small design choices permeate through the entire system. For me, that’s the fun zone, where riding, camping, and design insight overlap.