Post Carry Co. Transfer Case: Travel, Flexibly.

Thursday, August 4, 2022

“How was it? Was it ok, or did it suck?”

It’s morning in Le Marais, Paris, and I’m optimistic as I ask Danielle, my wife, how her transit from Nice went. I arrived last night around 23:30, tired and somewhat disoriented by the night lights and street scenes I rode through one-handed, navigating with google maps on my phone. I should have arrived earlier, but had to sit around in Lyon for hours for a train with a spot for my bike on it. I’d just spent 3 days riding over the Alpes from Nice; Danielle, had flown over with the kids on August 1.

“It didn’t suck. It was ok, just sort of floppy. Compared to the other ones, it was night-and-day better.”

As I try to gauge Danielle’s response it’s obvious she’s too tired to be anything but direct. This is actually not the sort of thing she’d pull punches about, because the struggle and frustration of multi-modal travel with bike cases is visceral. A special alchemy of stress, anxiety, and uncertainty makes folks HATE moving bikes around in cases. And I mean HATE. Like, ‘I’m going to throw this thing in the canal.’

To this point in our 4-week trip in Europe, I’d been really happy with my new Transfer Case. During our first trip to the continent in 2018, I didn’t even consider doing a transfer from one locale to another by bike while Danielle and the kids travelled via plane or train. I’d borrowed a large Scicon case for my bike, and it was very cumbersome to get around in taxis, buses, trains and ferries; I know this because we did them all. The lowlights of that trip with the Scicon were carrying it for 15 minutes it on my back through Venice at 04:30 to the water taxi, with my bags on my chest, because the wheels wouldn’t roll on the cobble stones, and even if they did, would have woken everyone up and potentially gotten me stoned. Not in the THC sense. ‘Better yet,’ the case’s wheels melted - MELTED! - while pulling it over hot pavement to the airport in Nice. FFS. On top of the pure bullshit of trying to actually move this thing around, it also cracked on a flight, which required liberal reinforcement and duct tape to repair. So it was brutal to get around, and lacking in ability to do it’s primary job: protect my bike. Once home from the 5-week trip, the Scicon was dead to me. There had to be a better option.

I thought EVOC cases might fit the bill. I borrowed one for a trip to Victoria, BC, and it seemed good for that simple use: taxi - airport - taxi - accommodations - taxi airport - taxi — home. Basic, very little walking around with the thing; easy.

So I borrowed an EVOC for our 2019 trip, and made a plan to do a transfer by bike from Nice to Genoa. Turns our that soft-case was brutal for Danielle to move around as she and the kids took the train to Genoa. It was a visceral experience for her; she HATED that thing. While the ride I did with Scott and Nico was a phenomenal experience, Danielle made it possible by taking the bike case and my non-riding stuff to Genoa, and her experience was terrible. The ability to ride to our next destination instead of packing the bike up for a plane trip was contingent on having a setup that was at least ‘fine’ to get around. Fine would be ok if fine was actually a thing. My search for a solution that was at-worst fine led me to Post Carry Co.’s Transfer Case. At $400 USD retail, the case seemed like a potential godsend, IF it could deliver the protection required to match its apparent portability. I reached out to Marc Mendoza, the brand’s creator, and we worked out a discount that worked for both of us, which enabled me to jump in, take a bit of a flyer, and find out whether this true soft-case approach is rad or risky.

Cycling is AWESOME because it’s emotional; emotion cuts both ways.

Cycling is many things to many people. At its core, it’s about emotion. It’s a hard sport / practice, and it necessarily and inevitably involves struggle, pain, and suffering. The highest highs we experience manifest through contrast: fear and anxiety, pain and suffering, juxtaposed, through perseverance, against elation, satisfaction, relief, and joy. Nothing feels better than making it through difficult circumstances on energy derived from hope and faith.

The raw emotions we experience through cycling inform our sense of possibility, and over years of experience, calibrate our risk-reward equation. When we’re riding locally, we have bailouts. We have contingencies, options, fail-safes. If our bike breaks, getting home is where the drama ends. Traveling to ride bikes is radically different.

If there’s something resembling a common feeling associated with flying with bikes, it has to be anxiety. Maybe it’s a ‘the more you know the more you worry’ thing; maybe not.

In the weeks and days leading up to air travel I’ve always been stressed out. The first time I flew with a bike was to Vancouver, and I was fairly oblivious. I showed up to the airport with my MTB, pedals off, bars turned 90 degrees, and collected a heavy-duty plastic bag to place it into. It seemed prone, but I’d been told that this approach generally works well, so I crossed my fingers as it disappeared from view. I didn’t have a clue that bikes are just like other cargo; they often don’t make it onto the planes they’re supposed to. Ignorance is bliss? Not entirely; I was definitely worried my bike would be damaged. And it was, but only slightly; nothing I couldn’t fix in about 10 minutes. On the return flight the bike fared better, phewf!

Portable, Protective, Inexpensive: Pick Two?

It would be years before I’d fly with a bike again, and as a relatively one-off occasion, I was happy to borrow a hefty hard-case from a friend and put my (custom steel) road bike in there along with tools, shoes, etc., and wrestle it into a taxi or whatever. It was big, hard to move around, and very protective. There wasn’t much to go wrong with that setup, but it sure was challenging to transfer through transportation modes. With peace of mind regarding bike security came significant transportation challenges.

Similarly, the Scicon hard case I borrowed years later for our first family trip to Europe was fairly protective….when it was intact. And extremely difficult to move around. As in, “Holy F, I HATE this thing!” Getting that case into cars was tough, but not as tough as moving it around on cobble stones! And then there was the melting…. At the same time, my riding experiences during that trip (France, Greece, Iceland) were spectacular, and I’d accept the struggles to do it all over again. A couple insights flowed from that trip:

Clunky hard-cases are great for peace-of-mind, but carry compromises: heavy, big, cumbersome, and breakable (hard plastic is great until it cracks, which is inevitable).

The benefits of hard cases are inversely proportional to the number of transfers you’ll do during a trip. Meaning, if you drive to an airport, fly, drive to accommodations, hunker down, then repeat, a hard-case is ideal. Add on extra transfers between accommodations/locations and additional modes of transportation - cars, trains, ferries - and the ‘Yass-factor’ for a hard-case quickly drops, then flips into ‘bane-of-my-existence-factor.

The bike and ‘flight-system’, when coupled, form a dynamic that determines the art of the possible. In simple trip scenarios - like flying in and out of the same city, staying at one accommodation - a hard-case doesn’t limit bike riding opportunities in any way. On the contrary, the maximum protection of a good hard-case, and often limited bike disassembly required translates into maximum potential for bike riding good times. Your bike is very likely to be perfectly fine, and relatively easy to put together and ride. Yay!

The more flexible you want to be in a foreign locale, the more constraining hard-cases become. Moving accommodations within a town or city, which isn’t a total rarity, it a shit-show with a hard-case, and even a soft case like EVOC’s. ‘Do I tear my bike down and pack it up, or make two trips?’ I’ve done a transfer like this with my bike in one hand, case in the other, bag on my back, and let me tell you, it SUCKS! What about taking the train to another locale, which is super easy with normal luggage? Again, do I want to go through the hassle of packing the bike up, or struggle with it and the case at once? The overarching realization many arrive upon in Europe is that getting around via train is WAY easier in many countries than in North America, and while short flights are ludicrously inexpensive, riding 200km might not take WAY more time than a flight, when you factor all the security stuff and bike packing stuff. And if you take a train part-way to a destination, you can ride the balance. But if you’re travelling with a hard-case, you wind up tied to it, and for me, this is aggravating.

It’s not necessarily realistic to expect to fit into one or the other rider category. Many will begin cycling travel with ‘simple’ itineraries, get the feel for things, build confidence, and want to expand into more complicated adventures. Trying to determine what sort of travel solution for the bike will be optimal for the rest of your riding life is probably an exercise in futility.

The keen reader will note that I’ve not mentioned anything about the cost of checking a bike in the Transfer Case versus the other four ‘systems’ I’ve used. Since the pandemic, most airlines have tightened up on all baggage charges, even charging for carrying-on anything beyond what one can fit under the chair in front of them. Once upon a time, using the Transfer Case could have enabled a rider to check their bike as a mere piece of luggage, and forego oversize, let alone ‘bike’ charges. In my experience, each airline we flew with in 2022 charged us for the ‘bag’, as ‘oversize’ in some cases, and ‘bike’ in others. Policies are all over the place, and generally you’re at the mercy of the person processing the item. There were no free checked pieces in 2022, so it wasn’t really much of a jump to ‘oversize’. That said, you’re more likely to avoid a gouging ‘bike’ fee with the Transfer Case, as it' doesn’t really scream, ‘I’m a BIKE!!!!” Other cases sure do. Cha-ching.

Let me cover the triad in question here, starting with Portability.

Portability

If you’ve read this far, you understand why I’m putting a high premium on portability, which has two facets: bike within, bike without. You probably also already know that the Transfer Case requires more bike disassembly than most others. The ‘big deal’ with the case is that the bike’s fork must come off, in addition to both wheels, pedals, saddle/post, rear derailleur, and chain. The bike’s overall length with the fork out determines case size: Large or XL. My T-Lab gravel bike has a 59cm top-tube, which requires the XL size. Removing the fork significantly reduces the case’s overall dimensions AND contributes to bike safety. I’ll address this in the next section.

Bike within, the Transfer Case is unequivocally far easier to move around than any other I’ve used. The overall dimensions are quite small, and the case’s multitude of handles allow for easy lifting into and out of cars, etc., without having to resort to contortions. The handles are VERY sturdy and fit for purpose. The case supports its own weight well standing up, and doesn’t need to be one way around over another.

Walking affords two styles: bike trailing, bike leading. For me, bike leading was the most efficient way to move over any distance. I walked kilometres in Barcelona this way without discomfort. In contrast, while pulling the bike, each hand option wasn’t quite right for my height and arm length, so it was inefficient. While pushing, I would hold the middle handle and stabilize the structure with my other hand lightly guiding the top corner. Given the case doesn’t have a rigid structure, the case can squirm around a bit in relation to the wheels, which gentle stabilization addresses well. Even more, this stabilization allows me to maintain balance over the wheels so my arm isn’t taking the weight, the wheels are. Sometimes the wheels can run into a crack or whatever, causing an endo, like while riding; stabilizing with the upper hand controls this.

The ability to push the bike and have the wheels handle the load is what makes walking around with the TC in front far easier than pulling it or any other case I’ve used. I’m totally fine with walking 2-3km with it; easy.

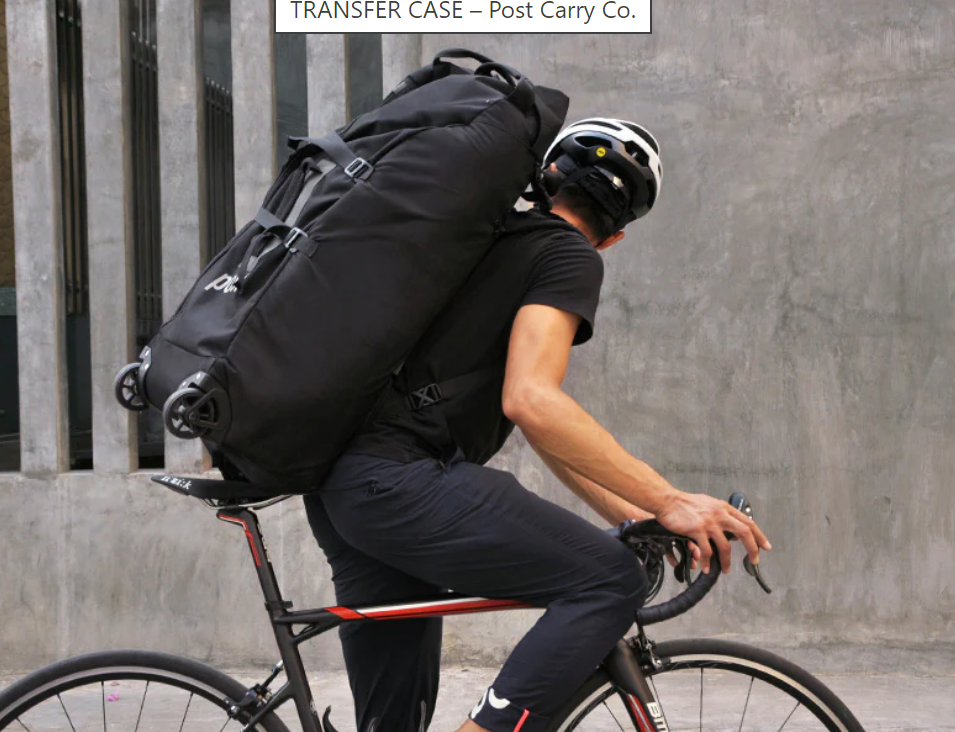

With the bike out of the case, yes, you can roll it up and turn it into a backpack. This is a great feature, and in reality, I’d expect that doing so would tend to also entail putting other stuff into it. For example, If I was solo, I’d be travelling with my backpack to carry-on, and the TC with my bike, tools, and the clothing. My pack would have everything required to ride - shoes, helmet, kit, basic on-bike tools - and my electronics and essentials. This is how I packed for Europe in 2022. In the TC went the bike, spare tire, more tools, spare parts, and rest of my clothes.

If I were to fly into Paris, then take a train to Grenoble, for example, and needed/wanted to ride my bike for some distance with all my stuff, I could do that. I’d have to put my backpack and all that extra stuff into the TC, roll it up, and wear it on my back. I can’t see this being super comfy, but why would you do this for any real distance? I wouldn’t want to.

The more pertinent question pertains to how easy it is to roll the case around with all that stuff inside, while the owner of all that stuff is off riding.

To prepare for this approach, I packed all my stuff into the TC in readiness for Danielle to fly with it. Without the bike within providing structure, it wasn’t a terribly stable form. It seemed ok; I hoped it would be ok. As it happens it was ok, but not great. Danielle indicated that if it had been less floppy, it’d have been better. But it wasn’t ‘BAD’.

This is the sort of thing where one might say, ‘Ok, I’ll figure that out for next time.’ But let’s get real; not likely. In reality, all that stuff gets put away, and only comes back together as packing for the next trip unfolds, which is inevitably stressful. The likelihood of adding a trial into the mix is low, so experimenting is more likely to happen at crunch-time, while away. Toward this end, I will offer a few suggestions, at least one of which I will try to try in 2023.

Collect a big cardboard box while you’re out and about, pre-transfer, and use it to structure the case. Clearly, this idea is totally hit-or-miss. But it could work. More practicable, perhaps, is to pack an extra inner tube, ideally a 29er one, and air it up inside the case to add structure. This is my ‘genius idea’ that might totally flop. I’d love to hear if anyone has tried this, or other moves.

Bottom line, if you want a clear judgement on the TC’s portability, it’s simple: YES. It’s very portable, in each mode, and as close to ideal as I know is possible. There’s room to improve on it while packed with ‘other stuff’, which I aim to advance.

Let’s not pretend the bike disassembly required to achieve this portability is trivial. It’s not. As a former shop mechanic, I am probably more comfortable working on bikes than the vast majority of riders out there, so my concerns about disassembly are more about wear and tear on threads and carbon materials than ability to do the work right and in a short amount of time. If the bike work required by the Transfer Case pushes you into anxiety, this isn’t good. If this is the case, and there’s also a wish to leverage the TC’s portability some time in the future, I suggest setting that as a goal, and working toward it piece by piece, starting with remove and installation of the bike’s simpler components: saddle and post, rear wheel, pedals, chain, rear derailleur. The fork and front brake (which doesn’t necessarily have to come off) is the last piece of the puzzle to work on getting comfortable with. Everyone can learn. As with anything, be it a new language or technique, a degree of necessity and urgency drives focus and comprehension. If you want to learn this stuff, and you need to learn this stuff, you can learn this stuff.

Protection

Portability without sufficient protection is pointless. Once you hand your bike over to airport staff anything can happen. It’s not uncommon to hear of bikes being thrown onto the tarmac from baggage compartments, and piling other luggage on top of them is pretty much a given. Our bike cases have to be robust from every angle. As I was drafting this piece I posted an Instagram story about it, and opened the door for questions. No surprise, a follower responded: “Soft case? I’d be so worried. I went with a Scicon hard case. Was not cheap, but here we are.” I get it, hence the deep dive here.

Out of the box, the Transfer Case’s protection approach was impressive. Marc Mendoza, the man behind Post Carry Co., seems to have thought of just about everything, which is borderline unheard of. There’s '(at least one) a place for everything, and the instructions provided are clear and simple to follow.

For reference, take a look at Bicycling’s web piece on travel cases. You’ll get a sense of the range of options out there - you probably already know since if you’ve read this far - and the range of prices. You’ll note the Orucase Airport Ninja is comparable to the Transfer Case, requiring the same bike disassembly and similar case features. That’s where the similarities end, in my view. The protection offered by the Orucase strikes me as inferior to the TC.

Fork Off ?/!

While some folks will cringe at the thought of removing their fork to pack up their bike, and likely consider other solutions that forego this step ‘superior’, I would argue this is a matter of priorities.

My priority with respect to protection is to have my bike as close to immune to damage while in the case as possible. Does this mean I need to compromise convenience when packing and rebuilding the bike? Yes. I’m happy with this compromise because removing the fork drastically reduces bike-destruction potential. What?

Most case designers are starting from assumptions about their customers. Most customers, they assume - fairly - don’t want to mess around with their forks. Fewer parts off the bike equates to marketing ‘features’. From this orientation, cases must be built BIG and with LOTS of structure.

I don’t like the big cases for portability, but are they better for protecting your bike? Hard to say, category-wide, but I can certainly attest that a soft-case like EVOC’s is a risky proposition, because the bike’s fork functions as a long lever situated in a corner of the case, relying on a rail that extends from fork mount to rear dropout mount to resist the force of impact on either corner. Meaning, If this case is dropped on the corner the fork’s dropouts sit in, it is unequivocally possible that force will damage the fork, headset, and/or frame. The rail relied upon to resist this force is actually commonly bent in the middle over repeated use, which reduces its ability to resist further bending.

When using EVOC cases, crushing was my primary concern, along multiple angles of attack. At the same time, the case was not easy to move around, even/especially when it didn’t have my bike in it. In contrast, the Transfer Case has us remove the fork and stash it in a sleeve along hefty foam padding (you can see it adjacent my bike’s downtube in the image below). The fork is not prone to damage where it’s stored, and there is no longer a long lever in play that can amplify force and damage.

Ok, so what about the head tube; is it now our primary failure point? No. As you can see in the image above, I’ve bagged up the headtube, which captures the headset parts. There’s a gap within the corner of the case, which I filled with high-density foam from my collection. The thick foam padding against each headset cup would absorb a sledge hammer blow, in my estimation, so I have zero fear about harm. In the event of a drop onto the corner of the case the headtube sits in, I wanted to add more energy damping. I’m very happy with the result of my small addition. Zero fear.

Dropout Loser?

Obviously, we need to take our back wheel out. A bike frame, fully built up, is pretty tough. You can crash it all sorts of ways without harming it. But take all the components off, and sensitive areas are exposed. The headtube’s bores/holes are prone to denting, which I address above. The seat-tube opening is prone to denting unless it has a collar on it, in which case it’s not really a big soft-spot. The bottom-bracket shell is prone to denting until it has a bottom bracket in it. Then it’s darned tough. The rear hub dropouts, with a hub mounted, can be stood on without inflicting harm. Take that hub out and it will generally be easy to crush them together under load. This is why protecting my rear dropout assembly became my primary concern after sorting out my headtube area.

The TC’s protection for the rear dropouts is good, and carefully executed. As you can see from the image, the dropouts nest into the corner of the case that supports its robust wheels. These wheels are mounted to a rigid corner junction, but it’s not ‘rock-solid.’ This means it is possible to crush the corner under load, which would push the dropouts together. This isn’t ‘likely’, but it’s possible. To manage this risk, I used an alloy dummy-axle, bolted in with my thru-axle. This mimics a rear hub, and makes the drop-outs virtually uncrushable. A PVC plastic tube would also work well for this job (both types come with some new bikes these days, when shipped with the back wheel off), but I use the tube as a lever-bar on my multi-tool for removing pedals, so metal is necessary.

Introducing this reinforced and rigid structure into the mix carries a consequence: the chainstays are now the next point of failure under crushing load. However, since they are narrower than the case’s side panel below, AND wheels sandwich the chainstays, the likelihood of bending them is incredibly low. As in, it would probably need to be run over by a truck. I’m good with that.

Chainring Zone

Chainrings are pretty tough, but they are not build to take heavy side-loads, and smashing them vertically can obviously harm their teeth. As you can see in the images, there’s lots of room around my ring to add foam if desired, or other items, like bags of clothing, shoes, etc. My case was ultimately packed absolutely FULL with items my family members had bought over the trip, mostly clothing: “Dad, you you have room in your bike case for this?” “Yeah, I can make it work!” Almost every void within the case was filled, and the wheels sandwiching the bike guarded the chainring from side-load. I think my wheel’s would have to be crushed in order for the ring to be damaged. In that case, the ring would be the least of my concerns. The included chainring and chainstay guard will help ensure the ring doesn’t cut up other things in the case.

Handlebars and Stem

You can see in the images that I’ve removed my front brake from my fork, and I’ve also freed my rear-derailleur cable housing and rear brake line from their cable guide under the downtube. This external routing is not the default specification from T-Lab, as most folks want the cleanest routing possible, which runs lines through the down-tube. My priority was ease of safe packing and swapping out components quickly, so I went external. This allowed me to really free up my handlebars to go wherever they needed to avoid damage to them and my levers, or avoid inflicting damage on wheels or other parts. I was very happy with the result, and didn’t worry about the setup at all. If you’re running wireless shifting this becomes even easier, but it’s worth considering the limitations of certain routings and options for positioning your bars where they need to be. In general, ‘fully-integrated’ front-ends, which route lines through handlebars and head-sets will be VERY difficult to fit into the Transfer Case or any case that required handlebar removal.

Wheels

If there’s one soft-spot in the TC’s protection game, it’s wheels. As the ‘bread’ of the bike sandwich, the wheels are subject to compressive loads, and don’t have tire pressure to rely on for a degree of protection. In my mind, alloy wheels are generally shallow and robust enough to render this potential failure mode very minimally concerning. Realistically, this potential for damage probably only really raises its head for riders who actually have wheel options. For example, I had three different carbon wheel options I could take to Europe in 2022 to run 35mm Rene Herse Bon Jon tires on, and all were Woven Precision Handbuilt carbon rims: 35mm, 50mm, 55/65mm. My deep wheel option ruled itself out, as there’s no point rolling up and down mountains with deep wheels. The G50s are my favourites, as they combine a wide stance for the tire with low weight (mine are an extra-light variant) and stable handling. However, with more surface area than the 35s, and being a thinner carbon construction, I felt like I’d be asking for it if I packed them. This compromise highlights the case/bike dynamic at the core of the travel experience; more on this in the next section.

For 2023’s trips (Nice, France in April, Italy in July), I would like to take my G50 wheels. In order to do so without anxiety, I’ll work on devising a bit of extra protection in the form of rigid plastic or cardboard. This will limit the bag’s ability to roll up on itself, which won’t be an issue for the first trip, but could be for the second. Keep an eye out on my Instagram profile for updates; I’ll have a story archive for the Transfer Case.

Inexpensive?

I’ve expressed how portability and protection are not at odds with the Transfer Case, which leaves the matter of expense. Are we looking at a bike case situation akin to the equation we apply to bike frames and components: LIGHT, STRONG, CHEAP: pick two. Does the same apply with bike cases: PORTABLE, PROTECTIVE, INEXPENSIVE: pick two?

I’m not aware of a hard-case for ‘normal bikes’ that is PROTECTIVE and INEXPENSIVE. We know they are not PORTABLE. Sure, there are PORTABLE options that are INEXPENSIVE, like the plastic bag I used on my first ever bike flight. Or there’s this thing, Bud’s MTB Bag, that I guess would be perfect for the train (many trains in Europe require you to bag your bike), but woefully inadequate for flights.

If you go the route of a breakaway frame and case, you’ll get PORTABLE, PROTECTIVE, EXPENSIVE. That dedicated travel-bike approach is ideal for some folks (particularly those who stick to pavement), but not appealing to those who’ll fly once annually or less.

The Transfer Case retails for $400 USD. Marc sold me mine at an industry discount price, on the understanding that I’d write a piece about it capturing my experience. By no means did Chris expect an ‘ad’. I was confident going into this that I’d be happy with the TC, so it didn’t feel like a ‘risk.’ The TC was the ONLY compact soft-case I considered protective enough to trust my bike to.

I’m not going to tell you that $400 is ‘cheap’ and you ought to ‘just go for it.’ My objective is to provide all the information I can to help you make a decision you’re happy with long-term. In my mind, $400 USD is an absolute bargain. I would 100% pay full retail for another TC if mine vanished. In a heartbeat.

Never, ever, had I looked at bike case and said to myself, ‘Damn, I really like this thing.’ Never. Based on my prior experience, I didn’t know it was possible to have a positive emotion association with a bike case.

There’s a leap of faith associated with putting your bike into a soft-case. I’ve done what I can here to enable you to make an informed decision around whether you feel good about that leap. If we look at the hard-case end of the spectrum, brands are selling us, ‘certainty.’ That’s the pitch, anyhow. They know fear and anxiety underpin decision making in this domain, and the higher the price of their product, the more protective it must be, right? Debatable. Everything breaks. A rigid structure with wheels mounted to it has a weakest link, and that link is often the wheels. Ok, so wheels break, but your bike is fine. Cool. But how do you feel about travelling with your bike when you have to carry your hard-case on your back through Venice at 04:00? As I said from the outset, we travel in different ways. If transfers are not your jam, and you don’t want them to be, cool; a hard-case might be ideal for you. If you want to open up opportunities for flexible multi-modal travel, the Transfer Case is PORTABLE, PROTECTIVE, and INEXPENSIVE, compared to other options that are at least PROTECTIVE.

Bottom Lines and a bit of Philosophy of Technology

If it’s not already obvious, I am entirely happy with the Transfer Case, and I’m looking no further for a travel solution. I have a couple adaptations to work out toward what I’d consider a ‘perfect’ setup, which might or might not be relevant to other riders. I don’t think there’s one perfect case for every rider, let alone one perfect case for all. In other words, by no means should we want a solution that claims to offer ‘something for everyone.’ In contrast, I think we ought to aim for a product that delivers on the claim to be ‘everything to someone.’

Hard-cases that deliver incredible protection and minimal bike work are going to be ‘everything to someone.’ I’m not that person. Are you? If so, your travel plans will have to conform to the limitations of such a system.

The Transfer Case is ‘everything to someone’: me. If your priorities and capabilities are similar to mine, it could be everything to you too. It might be worth zooming out to 10,000 feet to assess what your ‘everything’ is. This is where the matter gets next-level holistic.

An overarching orientation I maintain, which informs all my decision-making about bike tech, is built upon a long and deep foundation of experience, spanning more than 30 years. I’ve had SO MANY bike parts and bike frames break over the years, I don’t have any illusions about magical durability. I’ve worked on thousands of bikes, and have seen the whole spectrum of ways tech can fail. I used to FIX bikes and bike parts all day, 5 days a week, which often involved repurposing, adapting, improvising, and sometimes innovating. Consequently, I put a high premium on repairability, which, combined with a prior and longstanding urge to ride bikes every day, has culminated in a strong bias toward mechanical systems and non-integrated bikes.

Non-integrated isn’t where the bike industry is going. In contrast, Apple’s concept of ‘plug and play’ has permeated technology domains well outside of telecommunications and electronics, mainstreaming the concept of integration, nested within the concept of seamless user-experience. In this conceptual space, walled garden ‘ecosystems’ have grown/developed around brand aesthetics, values, operational requirements, and optimizations, in some order of priority.

As you might be thinking, optimizations associated with energy systems (batteries in particular) have driven manufacturers away from ‘interoperability’ HARD, and toward proprietary integration. Apple’s Lightening charger is a perfect example. It’s optimized for their battery tech, which is controlled by proprietary programming (Apple’s IP). If battery life is a metric that can be marketed as a ‘feature’, Apple will want to lock down what they are doing to optimize it. Within their ecosystem of tech, you’re good to go with a Lightening charger as long as you stay on-brand. This is a tech integration incentive to be and stay an ‘Apple person.’ They started doing this with their laptops years ago, which ‘just worked’. If you consider how Tesla builds their cars, all the same dynamics pertain. From a lifecycle management perspective, this integrated stuff is not great. Backward compatibility is NOT a design goal, in general, so there is a persistent and enduring push/pull to replace products with the next gen.

Bikes are going the same way across all categories. I’ll not argue that we should all want or we all need the same type of tech - integrated, not integrated, etc. Fundamentally, performance bicycles are luxury goods we purchase based on emotional states and emotional aspirations. Integrated bikes, with brake and shift lines routed through bars, stems, and frames look amazing, and this generates positive vibes in many of us. This isn’t ‘right’ or ‘wrong’; it just is.

A ‘good bike’ for some folks, be it a road bike, mountain bike, or whatever, is a bike the rider wants to ride. In my region, the only road bike I want to ride for a pure road route is one that is aero-optimized, geared to go fast, deep wheels, and an aggressive body position. That’s a bike I’d be excited about riding, and one I’d be happy to run fully integrated with electronic shifting. However, this isn’t the sort of bike I’d want to fly anywhere with, because pure road bikes are far too specific a tool for the riding I do in Europe or elsewhere. With the majority of my ‘fun budget’ going to family travel, I can’t justify a spend on a modern, integrated road bike.

For riding I want to do in an open and flexible way, I need a bike I can look at and want to ride that is also suitable for flying, reliable, and repairable. This means not-integrated, and it means ‘interoperable’. Meaning, I can go to any number of bike shops wherever and keep the bike rolling.

My T-Lab is built to strike a balance of travel-readiness and reliability with performance I want to the bulk of riding it’s used for. Flexibility is what I’m striving for - which is a key facet to manifesting an ‘open approach’ to riding, versus a ‘programmed approach’ and have achieved with my first T-Lab X3 build. As I near welcoming the next iteration X3 into my life, the same values carry forward. The bike will be built to keep possibilities open, and the Transfer Case will match its polyvalence.

The dream some of us aspire to realize is to own a limited number of bikes that are TOTALLY dialed. As I mention above, I’d love a totally dialed road bike for local riding, and since I wouldn’t want to travel with it, I could live with all sorts of integration on the bike. Riding in Europe is the absolute highlight of my year. I never feel more ‘myself’ than when I spend weeks waking up early, getting dressed, and getting on my bike to ride in the early light into mountains. As I write this I get emotional about the beautiful experiences I’ve had on these trips, and the feeling of being exactly where and how I need to be. 2022’s transfer from Nice to Paris was an experience I treasure, and it was possible because Danielle was able to take my Transfer Case from point to point for me.

The thought of taking an ‘old bike’ or ‘beater bike’ for weeks of riding overseas, because I don’t want my ‘good bike’ to be damaged repels me. I rode more than 100 hours during out 2022 trip, and asked a lot of my bike. Paramount, while riding in the mountains, is reliable braking. The drivetrain gets worked. Tires have to be new or near-new, and simple stuff like breaking a spoke becomes a real hassle when working with limited tools and out of an Air BnB kitchen.

I want my all-road bike, which I ride the vast majority of the time at home, to be totally dialed for local and travel riding. I cover a lot of terrain; the bike’s ecosystem is quite broad geographically and morphologically. Its polyvalence renders it a commensurately suitable bike for riding in Europe, provided I maintain flexibility in cable routing and don’t commit myself to ultra-light rims I can’t adequately protect. As discussed elsewhere, it remains to be determined whether I’ll chose to pack my light G50 wheels for then next trip. If this is the one concession I have to make, I’m more than ok with it.

To sum up, our bikes can be walled gardens if we want them to. Similarly, the solutions we steer ourselves into to move these bikes through the air can function well within a closed ecosystem. The optimizations that underpin each - bike and case - render them highly functional within a confined use-case, but lacking the flexibility and resilience to thrive outside of their habitat.

Multimodal travel with bikes is about leveraging complex transportation networks to enable fluid, expansive, enriching, and adventurous cycling experiences. Some bikes and travel cases lend themselves well to the broad and permeable view of cycling possibility; others don’t. We’re all on our own journey through cycling, and I don’t want to be prescriptive. I hope this piece helps inform sound decision making, whatever your priorities, challenges, and aspirations. Please let me know below if there’s anything I’ve left out.

Thanks for Marc Mendoza for helping me dive into the Transfer Case without feeling like I was taking a big risk. Phenomenal work, Marc, respect!

Post script: Charges for your bike can get ludicrous with some airlines. Luthtansa charges $300 CAN! Refer to this link to assess costs across solid range of carriers.